'Far from the Madding Crowd' by Thomas Hardy

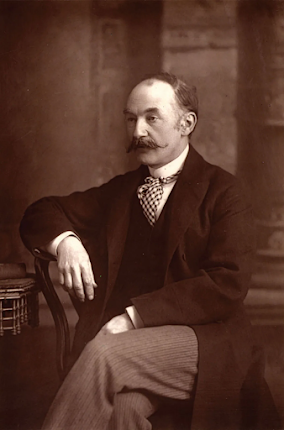

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy was born on June 2nd, 1840 in the village of Higher Bockhampton (Southwestern England). His father was a stone-mason and a violinist. His mother enjoyed reading and retelling folklore and legends popular in the region. Rural living, with its cyclical nature and strong oral culture, profoundly shaped the author. From his family and origins, Hardy gained the interests that would influence his life and appear in his novels: architecture and music, the lifestyles of the country folk, and literature itself.

Hardy attended Julia Martin's school in Bockhampton between the ages of 8 and 16. However, most of his education came from the books he found in Dorchester, the nearby town. He taught himself French, German, and Latin. At sixteen, Hardy's father apprenticed his son to a local architect, John Hicks. Under Hicks's tutelage, Hardy learned about architectural drawing and the restoration of old houses and churches. Despite his work, Hardy did not abandon his academic studies; in the evenings, Hardy would study with the Greek scholar Horace Moule.

In 1862, Hardy was sent to London to work with the architect Arthur Blomfield. During his five years in London, Hardy immersed himself in the cultural scene by visiting museums and theaters, and studying classic literature. There, he began to write his own poetry. Although he did not remain in London, (choosing instead to return to Dorchester as a church restorer), he maintained his newfound talent for writing.

Historical Context of Far From the Madding Crowd

- Full Title: Far from the Madding Crowd

- When Written: 1874

- Where Written: London

- When Published: 1874, first serialized (anonymously) in the Cornhill Magazine and then in a volume edition.

- Literary Period: Victorian

- Genre: Novel

- Climax: Troy bursts in on Boldwood’s Christmas party to reclaim his wife for his own, and Boldwood shoots him.

- Antagonist: Sergeant Troy is beloved by his wife Bathsheba, and yet he is also the clearest antagonist—not only to her, but also to Fanny, Boldwood, and Gabriel, all of whom he hurts in various ways. One could also argue that Bathsheba is her own worst enemy, as it is her own actions (including marrying Troy) that lead to her unhappiness.

- Point of View: Hardy uses an omniscient third-person narrator, who moves throughout the various settings of the novel and even among points of view. The first part of the book hews closely to Gabriel’s perspective, for instance, but after he reaches Bathsheba’s farm, the text mostly stays close to Bathsheba’s own point of view to reveal her thoughts and emotions. The narrator, however, also moves between Bathsheba, Boldwood, Troy, and the “Greek chorus” of the farm hands at Warren’s Malt-house. The narrator also at times makes general pronouncements on the characters, women, and rural life as a whole.

Plot Summary

Bathsheba Everdene has the enviable problem of coping with three suitors simultaneously. The first to appear is Gabriel Oak, a farmer as ordinary, stable, and sturdy as his name suggests. Perceiving her beauty, he proposes to her and is promptly rejected. He vows not to ask again.

Oak's flock of sheep is tragically destroyed, and he is obliged to seek employment. Chance has it that in the search he spies a serious fire, hastens to aid in extinguishing it, and manages to obtain employment on the estate. Bathsheba inherits her uncle's farm, and it is she who employs Gabriel as a shepherd. She intends to manage the farm by herself. Her farmhands have reservations about the abilities of this woman, whom they think is a bit vain and capricious.

Indeed, it is caprice that prompts her to send an anonymous valentine to a neighboring landowner, Mr. Boldwood, a middle-aged bachelor. His curiosity and, subsequently, his emotions are seriously aroused, and he becomes Bathsheba's second suitor. She rejects him, too, but he vows to pursue her until she consents to marry him.

The vicissitudes of country life and the emergencies of farming, coupled with Bathsheba's temperament, cause Gabriel to be alternately fired and rehired. He has made himself indispensable. He does his work, gives advice when asked, and usually withholds it when not consulted.

But it is her third suitor, Sergeant Francis Troy, who, with his flattery, insouciance, and scarlet uniform, finally captures the interest of Bathsheba. Troy, who does not believe in promises, and laments with some truth that "women will be the death of me," has wronged a young serving maid. After a misunderstanding about the time and place where they were to be married, he left her. This fickle soldier marries Bathsheba and becomes an arrogant landlord. Months later, Fanny, his abandoned victim, dies in childbirth. Troy is stunned — and so is Bathsheba, when she learns the truth. She feels indirectly responsible for the tragedy and knows that her marriage is over.

Bathsheba is remorseful but somewhat relieved when Troy disappears. His clothes are found on the shore of a bay where there is a strong current. People accept the circumstantial evidence of his death, but Bathsheba knows intuitively that he is alive. Troy does return, over a year later, just as Boldwood, almost mad, is trying to exact Bathsheba's promise that she will marry him six years hence, when the law can declare her legally widowed. Troy interrupts the Christmas party that Boldwood is giving. The infuriated Boldwood shoots him. Troy is buried beside Fanny, his wronged love. Because of his insanity, Boldwood's sentence is eventually commuted to internment at Her Majesty's pleasure.

Gabriel, who has served Bathsheba patiently and loyally all this time, marries her at the story's conclusion. The augury is that, having lived through tragedy together, the pair will now find happiness.

Character's

Gabriel Oak

The novel's hero, Gabriel Oak is a farmer, shepherd, and bailiff, marked by his humble and honest ways, his exceptional skill with animals and farming, and an unparalleled loyalty. He is Bathsheba's first suitor, later the bailiff on her farm, and finally her husband at the very end of the novel. Gabriel is characterized by an incredible ability to read the natural world and control it without fighting against it. He occupies the position of quiet observer throughout most of the book, yet he knows just when to step in to save Bathsheba and others from catastrophe.

Bathsheba Everdene

The beautiful young woman at the center of the novel, who must choose among three very different suitors. She is the protagonist, propelling the plot through her interaction with her various suitors. At the beginning of the novel, she is penniless, but she quickly inherits and learns to run a farm in Weatherbury, where most of the novel takes place. Her first characteristic that we learn about is her vanity, and Hardy continually shows her to be rash and impulsive. However, not only is she independent in spirit, she is independent financially; this allows Hardy to use her character to explore the danger that such a woman faces of losing her identity and lifestyle through marriage.

Sergeant Francis (Frank) Troy

The novel's antagonist, Troy is a less responsible male equivalent of Bathsheba. He is handsome, vain, young, and irresponsible, though he is capable of love. Early in the novel he is involved with Fanny Robin and gets her pregnant. At first, he plans to marry her, but when they miscommunicate about which church to meet at, he angrily refuses to marry her, and she is ruined. He forgets her and marries the rich, beautiful Bathsheba. Yet when Fanny dies of poverty and exhaustion later in the novel with his child in her arms, he cannot forgive himself.

William Boldwood

Bathsheba's second suitor and the owner of a nearby farm, Boldwood, as his name suggests, is a somewhat wooden, reserved man. He seems unable to fall in love until Bathsheba sends him a valentine on a whim, and suddenly he develops feelings for her. Once he is convinced he loves her, he refuses to give up his pursuit of her, and he is no longer rational. Ultimately, he becomes crazy with obsession, shoots Troy at his Christmas party, and is condemned to death. His sentence is changed to life imprisonment at the last minute.

Fanny Robin

A young orphaned servant girl at the farm who runs away the night Gabriel arrives, attempts to marry Sergeant Troy, and finally dies giving birth to his child at the poor house in Casterbridge. She is a foil to Bathsheba, showing the fate of women who are not well cared for in this society.

Liddy Smallbury

Bathsheba's maid and confidant, of about the same age as Bathsheba

Jan Coggan

Farm laborer and friend to Gabriel Oak

Joseph Poorgrass

A shy, timid farm laborer who blushes easily, Poorgrass carries Fanny's coffin from Casterbridge back to the farm for burial.

Cainy Ball

A young boy who works as Gabriel Oak's assistant shepherd on the Everdene farm.

Pennyways

The bailiff on Bathsheba's farm who is caught stealing grain and dismissed. He disappears for most of the novel until he recognizes Troy at Greenhill Fair and helps Troy surprise Bathsheba at Boldwood's Christmas party.

Themes

Epic Allusion, Tragedy, and Illusions of Grandeur

Conflict and the Laws of Nature

Women in a Man’s World

Pride and Penance

One of Bathsheba’s principal weaknesses is her sense of pride, which (at least initially) is linked to vanity. When Gabriel Oak catches her looking at herself in the mirror, Bathsheba is simultaneously embarrassed and comforted by knowing that he’s seen her at her worst. Bathsheba’s pride suffers a number of other setbacks over the course of the novel, setbacks which she ultimately recognizes and accepts as proper ways of atoning for her earlier mistakes.

Bathsheba’s pride can also be linked to her thoughtlessness regarding other people: confident and impetuous, she dashes off a valentine to Boldwood without pausing to think of the possible ramifications of her actions. In another way, Bathsheba’s pride leads her down a difficult path and into dire consequences for herself. Carried away by Troy’s charm and flattery, she seems to decide to marry him for the sole purpose of rehabilitating her pride after he compares her to another, more beautiful woman.

No comments:

Post a Comment